The solitude required of mastery can be profound. Even for essentially social skills, a cultivation within is necessary, and time alone in analysis, imagination, and development equally crucial. When properly done, the isolated immersion is so complete, though, that time and space conspire in shrinking tight around you to form a total cocoon so that you seem to miss nothing in the broader world while that one thing is itself everything.

From the time of Plato and Aristotle, astute philosophers have sought the wisdom to understand what makes people feel their best, do their best, and become their best. In our time of massive uncertainties and daunting challenges, every organization of people working together needs to put the most effective tools of such wisdom into everybody's hands and minds. That way, people become much more hopeful, more engaged, more committed, more creative, and more productive because they're truly more empowered.

Wisdom is a force multiplier. Unwise choices never lead anywhere good. Ordinary mindsets aren't optimal for extraordinary times. Only the best of wisdom can bring us the resources for transformative innovation and genuinely excellent work in all its dimensions. The best leaders understand this and do everything they can to introduce the most practical philosophy to all their associates. And I'm grateful for that understanding, because it's allowed me to have a wonderful career for decades as an independent philosopher, bringing people exactly that. The right sort of philosophy isn't after all an elective luxury, but a required necessity for that excellence consisting in and produced only by the inner happiness wisdom alone brings.

One of the most important qualities we hardly ever think and talk about is the ability of self-renewal. We talk a lot about resilience and its important for a life of achievement and positive impact. And resilience, of course, is the capacity to bounce back after a hardship or disappointment and keep going. It's like practical equanimity, or the equivalent of emotional shock absorbers. What I have in mind with the quality of self-renewal is a bit different.

Whenever you're in a long-term quest or a demanding job, and you've worked hard, day after day for weeks, months, or perhaps even years, and nothing spectacular has yet happened to reward your efforts, you can begin to lose heart, or at least to lose whatever initial enthusiasm or energy you may have had for the project. Of course, if you're experiencing a lot of praise or admiration or encouragement from others, that can serve to keep you going through those long dry stretches of labor. But suppose that's rare or non-existent as well. What's going to keep you afloat? What's going to keep the wind in your sails, or the spring in your step? It's the quality and activity of self-renewal that does this. And it may be one of the rarest traits of all. But it's possessed by people who accomplish great and difficult things, despite any disadvantages they have, or obstacles they continually face.

Psychologists have recently written about the importance of a quality they call grit - the sheer ability to keep on going. But self-renewal is perhaps deeper and higher. It's the ability to keep going with a heart inspired and eager for the work, whether that work is household cleaning, bricklaying, business building, seeing patients all day long, or writing a book.

If grit keeps you going, and resilience picks you up, self- renewal helps you stay energized. And it's ironically easiest when you're working for something greater than the self. It comes from reminding yourself of your vision and values, and remembering how much you care. For many, it's an offshoot of practicing the presence of God. It's a way of recharging your heart and reconnecting with your inspiration.

How good are you at self-renewal? How good are the people on your team, or the members of your family? It's something worth thinking about, and cultivating.

The ancient Greeks advised, "Know Yourself!" I'd like to add, "Renew Yourself!"

The word 'glory' is interesting. It's old-fashioned. But it's important. Maybe it's even a key to our deepest fulfillment. And it's a word that's rarely used in our time.

I knew a man twenty-five years ago who brought it to work every day. He was a janitor, a custodian in a building of a hundred PhDs. He vacuumed up, emptied trash cans, and washed windows. But really, he was a custodian of souls. And when any of those PhDs was having a bad day, they went looking for him, for just a chat. To maybe feel, for a moment, something that could turn around their heart, and their day. It was something that shone through that man. And everyone felt it.

Glory. To me, it connotes a dazzling fullness of greatness and love. With that in mind, here's a thought. Maybe our highest calling is to bring glory into whatever we do. But we can't accomplish that when the smallness of a swollen ego gets in the way. Again, humility and nobility work together. Then you get, sometimes, glory. And everyone is lifted up. Amen?

In a Cadillac advertisement on the back page of the new edition of Esquire, we find this:

It is not the critic who counts: The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again; who knows great enthusiasms; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly.

It's an inspiring, shortened version of a famous statement by Theodore Roosevelt, worth representing in its entirety, because it's worthwhile to read and ponder the words again, and the additional thoughts and images that we all need to keep in view:

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

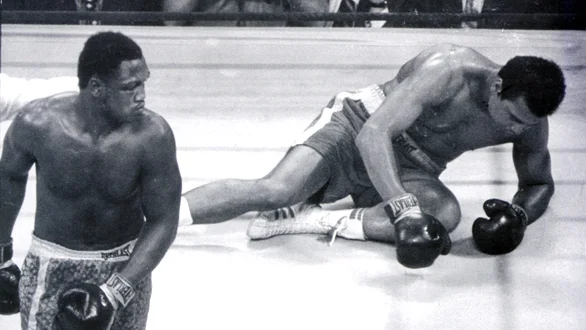

The Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca wrote vividly about a boxer who was bruised and bloodied in the ring, knocked down, but not knocked out, as being the only one who could bring to the next contest the deep confidence that never comes until you've had your teeth rattled and had the breath pounded out of you and outlasted the onslaught. The challenges, bumps, and bruises of life are to be used by us to strengthen our souls, and they alone prepare us for becoming and being the best we're capable of being. So, when they come, use them well, and proudly.

In the end, it's not the critics, but the struggling creators, who prevail.

People often find themselves in activities, jobs, and even relationships of various kinds that seem to do nothing but dissipate their energies and drag them down. And even when the negativity is subtle, it can be draining. Life is too short for that, and too important an opportunity. We're here to grow and soar. Struggle is certainly a part of life, as well. And it's often necessary for deep growth. But nothing's worse than unnecessary struggle or a situation that simply confines your spirit and dampens your fire.

If there's something in your life that often brings you down, or that seems like an uphill struggle, or clearly holds you back, it could be a problem you need to tackle and work through. It might indeed be a source for positive growth. Or at some point, you may just have to ask:

Does it feed my spirit?

Does it touch my soul?

Is it an important part of why I'm here?

And:

Can I do some good in this and still be fully who I am?

If the answer in each question isn't a resounding yes, then that might be a touchstone for change, a sign that you need to rethink what you're doing. The world benefits most from flourishing people, and not so much from individuals who are living at odds with who they really are. Sometimes, you need to rethink what you're doing, and shed what holds you back, in order to move closer to the light.

How intensely do you live? How fully embodied are you, throughout your day? Are you doing your thing All-In, or just semi-engaged?

Here's a challenging claim from Walter Kerr, in his book, The Decline of Pleasure:

"We are vaguely wretched because we are leading half-lives, half-heartedly, and with only one-half of our minds actively engaged in making contact with the universe about us."

Is that true of most people? Is it ever true of you, even half the time?

Just reading Kerr, I'm already vowing to make sure that, throughout this day, I'm playing life as a full contact sport, totally immersed, and committed to the full, with all my heart and mind.

How about you?

My motto for my work has always been simple:

Impact First, Then Income.

My primary concern is a positive impact. My secondary concern is a positive cash flow. And that matters, because the prioritization I try to maintain will suggest certain activities and discourage others. As a philosopher, writer, and speaker, I want to make a difference for other people, as well as myself, and my family. I want to put giving over receiving, spreading over gathering. Of course, finances matter. They matter a lot. But other things matter even more. And it's those other things that should be our ultimate guides.

But, I can almost hear a question, which is even, perhaps, a skeptical hesitation: Is this sort of perspective simply a luxury for the few - to think first about making a difference and only second about making a dollar? My answer is: No, I truly don't think so. No matter where we are in life or what we're facing, it's important to focus first on the contribution we're making, on the good we're doing. That's ultimately the best way to get help, or a job, or a promotion, or the big payday that most of us would like to see. But it's also right for its own sake. We're here to give more than we get, and to leave the world a little better than we found it.

I'm convinced that coming at the equation from the other end is always a mistake. Those who think first about making money and only second about making a difference will eventually encounter trouble in some form. And they'll risk not becoming the best they're capable of being.

Even if you work focally with money in a field like financial services, it's important to see beyond the the market and the monthly report. We all work with people. And that should fundamentally guide us. What's the real human benefit of your work? Is it everything it could be? is it what it should be? Will a certain decision enhance my impact, or only my income? Those are the questions we all need to ask. Money without meaning is empty.

How am I using my talents, my abilities, and my opportunities? What difference am I making for other people? Could I do more? Could I do better? Those are the fundamental issues. And then matters of finance can helpfully be raised. Income is necessary for most of us, and profit is good, if it fits properly into our overall lives and values.

Don't let the tail wag the dog. Put first things first. Focus on what you can do to bless and benefit those around you, and you'll see good come back to you in surprising ways..

"When your will is ready, your feet are light." George Herbert.

No job is harder than the one you don’t want to do. And no job is easier than one you love. Skill building is important in any profession. But will building is the key. John Ruskin once said, “When love and skill work together, expect a masterpiece.”

How do you prepare your will, what the philosophers called “volition,” for the job at hand? How can you move the will to love what you're doing?

The answer is simple. You do whatever you can to match yourself to a task that's right for you. And then you use your imagination. You envision its ultimate good. You put it into perspective, within the context of what you already love and care most deeply about. Only the heart can move the will in the deepest and most enduring ways. So prepare for your work by using your imagination to tend to your heart. Use the imagination well, and the heart will follow. And then, eventually, it will lead.

We can always find a reason for not liking, or not doing, a task we need to do. We can build up resentment, irritation, frustration, and even hatred by how we think. Or we can mentally put ourselves into a totally different state of being and doing. Its finally up to each of us. If you feel good about your work, it will feel much easier to you. Remind yourself of this simple truth when things seem tough, and pass on the insight to anyone you see struggling along.

Today.

"By the work, you know the workman." Jean de La Fountaine.

Cause and effect. A great guitarist plays a great solo. A master mechanic gets a car to purr. An original thinker writes original books. A salesperson who cares shows that care in her preparations, and serves her client like no one else.

The old view was that this is a matter of pride. Our jobs never define us. But the quality of the work we do will disclose us, reveal us, and give us away. It will also not just show who we are today, but in great part determine who we'll be tomorrow.

Do we do our best? Do we strive for excellence every day?

The great philosophers would have us recognize that all our choices define who we are. We're known for the quality we bring to the world. Let's remember that and pour our hearts into everything we do.

Today.

And tomorrow.

Hi everyone! Blogging this morning from the beautiful Wilmington, NC airport, preparing to board. I wanted to tell you about something interesting that came to light in the past few days.

The journal Nature reported this week that paintings of hands and animals in seven limestone caves on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi may be the oldest human art yet discovered. It's estimated that the people who did these simple paintings put their mark on the stone walls more than 39,000 years ago.

Since the beginning, human beings have wanted to make their mark in the world, to say "I was here!" I love it that so many of the paintings were outlines of hands. "This is me." Or, "This is my son." Or, This is my mate."

Those artists could have had no idea that we'd be talking about the hands and the animals they painted, more than 39,000 years after they made those simple, but inspired markings.

Likewise, we have no idea how far and wide our simple daily acts may reach and what impact they may have on others. The cave painters could never have predicted that their work would move us in 2014 to reflect on our own lives, and on how we make our own marks on the world.

And their lessons are many. One is that the smallest things can leap and fly across space and time with amazing results. Try to remember that in the little things you do.

Today.

Let's hear from Ralph Waldo, Quotable Quotes Guy, Emerson:

"Ideas must work through the brains and arms of good and brave men, or they are no better than dreams."

Yeah, and good and brave women, Ralph. Don't forget that.

My slogan for the big intro philosophy class I taught at Notre Dame for many years was “Ideas rock the world.” Because they do. But only through people and relationships.

My professional mantra is “Relationships rule the world.” No one ever accomplishes anything really important alone. It takes a network of friends and colleagues, collaborators and believers to make anything big happen.

We need to put these two insights together. As Plato saw, ideas are tremendously important realities, because they can lead the way into a better future. But ideas need to work through us every day in order to do their good in the world.

Do you have some dream of the future based on ideas about how things could be different? Don’t let it remain unrealized. Use your neural capacities to think out some supporting ideas - the implementation strategies you'll need. And then get into motion with arms and legs to make it happen.

You know the dream I’m talking about. Do something about it.

Today.

Ok. First of all, I have absolutely nothing against having a new idea go viral overnight and waking up to discover I have a new reality TV show, 5 million Twitter followers, a private jet, and a seven figure endorsement deal from the Library Association. That would be my definition of sweet (as defined also in dictionaries available nationwide in your local public library - I'd get 10K just for adding that little factoid. But I digress). Instant success has its charms. But, there is a nubby weave behind the smooth tapestry of most outsized success. And that, right now, is my concern.

Let me read to you from the actual paper version of today's New York Times Book Review. Turning through it, I came across a page entitled "Devilish Audacity" where John Simon reviews a new biography of Sir Lawrence Olivier (Olivier, by Philip Ziegler), who was said by many to be the greatest actor of his time (in addition to "the most dashing of actors" and "the most seductive of human beings" - among many other superlatives). Simon helpfully summarizes an important point in the new book about Olivier:

He was a tireless worker: It took him two years to learn how to move onstage, and another two, how to laugh.

That got my attention, and I would have laughed aloud, aside from the realization that I may not have worked hard enough as of yet on that particular vocal and facial expression of astonished surprise. Then, this:

On stage and on screen, he could give an impression of openness, brilliance, lightness, and speed. In fact, he was the opposite. His great strength was that of the ox. He always reminded me of a countryman, of a ... peasant taking his time .... Once a conception had taken root in him, no power could change the direction in which the ox would pull the cart.

Impressive. And suggestive. Behind many forms of flashy, flamboyant success, there is a lot of dogged, ox-like, hard work. Two years to learn to move on stage? Two years to learn to laugh? Yes. And as we go out onto our own dramatic stages, at work, or at home, or in the community, we should not allow ourselves to forget the hard work that alone will lift any performance to a distinctive level of power. In an age that celebrates the fruits of work without equally honoring or encouraging the work itself that typically makes those delights possible, we need to remind ourselves that the greatest never get that way without a lot of hard, hard work.

But if you love what you're doing, you can enjoy even the greatest efforts. The hard work itself can be a suitable and satisfying outlet for your energy. And - who knows? You can't really rule out that reality TV show.

The more forms of motivation you have for your work, or anything, the better - right? Well, not necessarily. A new study by Amy Wrzesniewsky, professor of organizational behavior at Yale, and Barry Schwartz, professor of psychology at Swarthmore, announced in today's New York Times, has found the opposite.

There are basically two forms of motivation for any behavior, or activity: intrinsic and extrinsic, or instrumental. With intrinsic motivation, you do what you do because you love it, or find it meaningful, or you value its natural innate rewards. With extrinsic, or instrumental, motivation, you engage in an activity because of external rewards you think it will bring, desirable things that are not inherently tied to the activity, but are promised to you for some form of excellence in that activity. As an example, when you're learning something new, you may be motivated intrinsically by the fascinating nature of the subject, or your own personal curiosity. You may value learning and growing and enriching yourself by the study you do. That's all intrinsic motivation.

In principle, you could work just as hard, even if you weren't that interested in the subject, or in the growth it would bring you, but just to get an A grade in a course, a 4.0 grade point average, Dean's List, and admission into your favorite next school along the way. That would be extrinsic, or instrumental, motivation, where the activity is being used as an instrument or tool for the attaining of something that's not inherently tied to it by its very nature. Someone not in school at all could be reading the same books, and doing the same analysis and memory work, where there were no grades, or lists, or future admissions at stake. That shows those rewards to be extrinsic, or not inherently tied to the activities in question.

Wrzesniewsky and Swartz claim that their research shows something interesting. Intrinsically motivated people do better over the long run than extrinsically motivated people. That in itself, or intrinsically, is interesting, and is a truth explored at length in Dan Pink's very nice book, Drive. But what's perhaps more surprising is the new body of evidence that adding extrinsic, or instrumental, motivation to an intrinsic interest, can actually be problematic over the long run, and degrade results.

How can that be? Isn't it always more motivating to add on an extra promise of reward? "Do the job well, and we'll give you extra credit, extra pay, a promotion, a cruise!" Well, it turns out that, no. The research being reported indicates that those who have both motivations for a longterm activity actually do less well than those whose motivations are simply intrinsic. Why? The researchers don't really say.

Let's suppose their study is right. How could it be that adding on an extra level of motivation for excellence in a longterm activity might actually be counter-productive? Well, one simple hypothesis is orientation conflict. People can't serve two masters, as the old biblical phrase has it. Whenever you have two distinct motivations, they can in principle come into conflict. There can be situations where there's a way to get the A, the Dean's List, the raise, or the bonus, that is actually out of step with what the intrinsically motivated person would do, and even more, where it's detrimentally contrary to a path of overall, longterm excellence. And because extrinsic motivators like prizes and grades and bonuses are available in the relatively immediate future, are commonly coveted, and appear, when they do, suddenly and dramatically, as well as often in a public way, they can easily begin to edge out the intrinsic motivator as what primarily forms your behavior. And this means that when there is a conflict, the wrong motivator wins.

People who love their work and find meaning in it tend to do better work than those who work only for the money. We know that. But wait. Does this new research show that we shouldn't pay people at all, lest we tempt them to serve two masters and do lesser work?

Not at all. There's a big difference between a consequence and a motivator. If a paycheck, or a royalty, or a financial return on investment of effort or expertise were not a part of the picture, most people could not afford to do the work at all. But the best people are often those who enjoy the consequence without being motivated by it. They do the work because they love it. They do it because it's meaningful to them. And, because of that, they do it best.

Secondly, this new research, at least, as it's reported in the Times, doesn't show that adding extrinsic rewards to intrinsic rewards can't in the short term enhance performance for a wide range of people. It's just problematic over longer time horizons where excellence is an issue.

Therefore, what?

Work for love. If you haven't already, then go find something to do that you love to do and would want to be involved in even if you weren't being paid for it. And then, when you can, make sure to hire people to do it with you who feel the same way. Create a keen sense of the excitement and meaning of the work - its nobility - both in its impact for good on others and in the fulfillment that comes to those who do it with world-class excellence.

Ironically, then your extrinsic rewards will tend to be greatest. Which just shows again that we live in a wonderfully crazy world.

I love the potential energy of an empty auditorium that's about to fill up with people. Anticipation is everywhere. You can almost breathe what's soon to be.

Whenever I'm going to give a talk, almost anywhere around the country, I try to get into the venue early, before anyone else is there, and feel the space. Seeing the space is important. But feeling it is even more crucial. For that, I have to use my imagination. What's it going to be like in the front row? In the back row? Off to the left, or the right? What am I going to have to do to fill this space and make sure everyone is involved and engaged?

Sometimes, I'll have a chance to actually go around the auditorium and sit in various places. I always did that the day before a new semester at Notre Dame, during my years as a professor there. I'd go into the auditorium, where, the next day, I'd greet three hundred new students. I'd sit in the front row, the back row, off to the side, in the middle, and just contemplate. I'd imagine what it would take to capture the attention and interest of the student in that seat. And then, the next day, I'd try to do it.

One evening, years ago, I stood alone in the middle of the Mecca, in Milwaukee, where the Bucks played basketball. The next day, I was going to speak to thousands of smart people, who would fill the seats, not for hoops, but for philosophy. My first few moments were intimidating. The space was dark, cavernous, and a little scary. I saw a sign that said "Exit" and that's exactly what I wanted to do - to leave the building, make my way back to the airport, and take the first flight home. How was I going to fill such an enormous place and keep everyone interested?

I decided to take charge of my thoughts and imaginations. I said to myself, "Tomorrow, I own this place. For one hour, this is my house. I get to decide what happens during that time. This is the place where ideas will flow, fun will be had, and hearts and minds will be recharged with positive energy." I didn't say it to myself as if I hoped that all this would be true. I said it as if I knew it would be. And I could instantly feel my emotions changing from anxiety to anticipation.

Emotionally, I like to take ownership of a space where I'll be working. If I can't get into the place ahead of time, I may look at photos of the building, and use my imagination even more. From doing my thing many times in big convention halls and sports arenas, and even an NFL stadium, I've learned the importance of owning a large space. But it's really no different in a small space. Do you have an important meeting coming up? If so, is there any way you can access the room in advance? Doing this allows you to feel the space and fill the space, project yourself into it, and imagine everyone else around the table, or throughout the room, smiling, or nodding, or connecting with you in some positive way. It creates a comfort factor, and an energy edge. It's almost magical, and even nearly spooky, how well this works. But, whatever else is involved, going into a place where you'll be "performing," and getting there early, allows you to take some of the unknown out of the equation. Smile. See yourself succeeding there. Then, you have a great head start on the event. When you own it, then you can use it well. It's up to you.